|

|

| Line 296: |

Line 296: |

| | SQA function (see topic 5, Software Configuration | | SQA function (see topic 5, Software Configuration |

| | Auditing). | | Auditing). |

| − | .

| |

| − |

| |

| − | [2*, c13] [3*, c13s9, c14s2]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | purchased software products, such as compilers

| |

| − | or other tools. SCM planning considers if and

| |

| − | how these items will be taken under configura

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion control (for example, integrated into the proj

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ect libraries) and how changes or updates will be

| |

| − | evaluated and managed.

| |

| − | Similar considerations apply to subcontracted

| |

| − | software. When using subcontracted software,

| |

| − | both the SCM requirements to be imposed on

| |

| − | the subcontractor’s SCM process as part of the

| |

| − | subcontract and the means for monitoring com

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | pliance need to be established. The latter includes

| |

| − | consideration of what SCM information must be

| |

| − | available for effective compliance monitoring.

| |

| − | 6-6

| |

| − | SWEBOK® Guide

| |

| − | V3.0

| |

| − | insights leading to process changes and corre

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sponding updates to the SCMP.

| |

| − | Software libraries and the various SCM tool

| |

| − | capabilities provide sources for extracting infor

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mation about the characteristics of the SCM

| |

| − | process (as well as providing project and man

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | agement information). For example, information

| |

| − | about the time required to accomplish various

| |

| − | types of changes would be useful in an evalua

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion of the criteria for determining what levels of

| |

| − | authority are optimal for authorizing certain types

| |

| − | of changes and for estimating future changes.

| |

| − | Care must be taken to keep the focus of the

| |

| − | surveillance on the insights that can be gained

| |

| − | from the measurements, not on the measurements

| |

| − | themselves. Discussion of software process and

| |

| − | product measurement is presented in the Soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware Engineering Process KA. Software mea

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | surement programs are described in the Software

| |

| − | Engineering Management KA.

| |

| − | 1.5.2.

| |

| − | In-Process

| |

| − | Audits

| |

| − | of

| |

| − | SCM

| |

| − | [3*, c1s1]

| |

| − | Audits can be carried out during the software

| |

| − | engineering process to investigate the current sta

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tus of specific elements of the configuration or to

| |

| − | assess the implementation of the SCM process.

| |

| − | In-process auditing of SCM provides a more for

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mal mechanism for monitoring selected aspects

| |

| − | of the process and may be coordinated with the

| |

| − | SQA function (see topic 5, Software Configura

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion Auditing).

| |

| − | 2.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Identification

| |

| − | [2*, c8] [4*, c29s1.1]

| |

| − | Software configuration identification identifies

| |

| − | items to be controlled, establishes identification

| |

| − | schemes for the items and their versions, and

| |

| − | establishes the tools and techniques to be used in

| |

| − | acquiring and managing controlled items. These

| |

| − | activities provide the basis for the other SCM

| |

| − | activities.

| |

| − | 2.1.

| |

| − | Identifying

| |

| − | Items

| |

| − | to

| |

| − | Be

| |

| − | Controlled

| |

| − | [2*, c8s2.2] [4*, c29s1.1]

| |

| − | One of the first steps in controlling change is

| |

| − | identifying the software items to be controlled.

| |

| − | This involves understanding the software config

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | uration within the context of the system configu

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ration, selecting software configuration items,

| |

| − | developing a strategy for labeling software items

| |

| − | and describing their relationships, and identifying

| |

| − | both the baselines to be used and the procedure

| |

| − | for a baseline’s acquisition of the items.

| |

| − | 2.1.1.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | [1, c3]

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | configuration is the functional and phys

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ical characteristics of hardware or software as set

| |

| − | forth in technical documentation or achieved in

| |

| − | a product. It can be viewed as part of an overall

| |

| − | system configuration.

| |

| − | 2.1.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Item

| |

| − | [4*, c29s1.1]

| |

| − | A configuration item (CI) is an item or aggre

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | gation of hardware or software or both that is

| |

| − | designed to be managed as a single entity. A soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware configuration item (SCI) is a software entity

| |

| − | that has been established as a configuration item

| |

| − | [1]. The SCM typically controls a variety of items

| |

| − | in addition to the code itself. Software items with

| |

| − | potential to become SCIs include plans, specifi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cations and design documentation, testing mate

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | rials, software tools, source and executable code,

| |

| − | code libraries, data and data dictionaries, and

| |

| − | documentation for installation, maintenance,

| |

| − | operations, and software use.

| |

| − | Selecting SCIs is an important process in

| |

| − | which a balance must be achieved between pro

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | viding adequate visibility for project control pur

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | poses and providing a manageable number of

| |

| − | controlled items.

| |

| − | 2.1.3.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Item

| |

| − | Relationships

| |

| − | [3*, c7s4]

| |

| − | Structural relationships among the selected

| |

| − | SCIs, and their constituent parts, affect other

| |

| − | SCM activities or tasks, such as software

| |

| − | building or analyzing the impact of proposed

| |

| − | changes. Proper tracking of these relationships

| |

| − | is also important for supporting traceability.

| |

| − | The design of the identification scheme for SCIs

| |

| − | hould consider the need to map identified items

| |

| − | to the software structure, as well as the need to

| |

| − | support the evolution of the software items and

| |

| − | their relationships.

| |

| − | 2.1.4.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Version

| |

| − | [1, c3] [4*, c29s3]

| |

| − | Software items evolve as a software project pro

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ceeds. A version of a software item is an identi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | fied instance of an item. It can be thought of as a

| |

| − | state of an evolving item. A variant is a version of

| |

| − | a program resulting from the application of soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware diversity.

| |

| − | 2.1.5.

| |

| − | Baseline

| |

| − | [1, c3]

| |

| − | A software baseline is a formally approved ver

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sion of a configuration item (regardless of media)

| |

| − | that is formally designated and fixed at a specific

| |

| − | time during the configuration item’s life cycle.

| |

| − | The term is also used to refer to a particular ver

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sion of a software configuration item that has

| |

| − | been agreed on. In either case, the baseline can

| |

| − | only be changed through formal change con

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | trol procedures. A baseline, together with all

| |

| − | approved changes to the baseline, represents the

| |

| − | current approved configuration.

| |

| − | Commonly used baselines include func

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tional, allocated, developmental, and product

| |

| − | baselines. The functional baseline corresponds

| |

| − | to the reviewed system requirements. The allo

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cated baseline corresponds to the reviewed

| |

| − | software requirements specification and soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware interface requirements specification. The

| |

| − | developmental baseline represents the evolving

| |

| − | software configuration at selected times during

| |

| − | the software life cycle. Change authority for

| |

| − | this baseline typically rests primarily with the

| |

| − | development organization but may be shared

| |

| − | with other organizations (for example, SCM or

| |

| − | Test). The product baseline corresponds to the

| |

| − | completed software product delivered for sys

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tem integration. The baselines to be used for a

| |

| − | given project, along with the associated levels of

| |

| − | authority needed for change approval, are typi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cally identified in the SCMP.

| |

| − | 2.1.6.

| |

| − | Acquiring

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Items

| |

| − | [3*, c18]

| |

| − | Software configuration items are placed under

| |

| − | SCM control at different times; that is, they are

| |

| − | incorporated into a particular baseline at a particu

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | lar point in the software life cycle. The triggering

| |

| − | event is the completion of some form of formal

| |

| − | acceptance task, such as a formal review. Figure

| |

| − | 6.2 characterizes the growth of baselined items as

| |

| − | the life cycle proceeds. This figure is based on the

| |

| − | waterfall model for purposes of illustration only;

| |

| − | the subscripts used in the figure indicate versions

| |

| − | 6-8

| |

| − | SWEBOK® Guide

| |

| − | V3.0

| |

| − | of the evolving items. The software change request

| |

| − | (SCR) is described in section 3.1.

| |

| − | In acquiring an SCI, its origin and initial integ

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | rity must be established. Following the acquisi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion of an SCI, changes to the item must be for

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mally approved as appropriate for the SCI and

| |

| − | the baseline involved, as defined in the SCMP.

| |

| − | Following approval, the item is incorporated into

| |

| − | the software baseline according to the appropriate

| |

| − | procedure.

| |

| − | 2.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Library

| |

| − | [3*, c1s3] [4*, c29s1.2]

| |

| − | A software library is a controlled collection of

| |

| − | software and related documentation designed to

| |

| − | aid in software development, use, or maintenance

| |

| − | [1]. It is also instrumental in software release man

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | agement and delivery activities. Several types of

| |

| − | libraries might be used, each corresponding to the

| |

| − | software item’s particular level of maturity. For

| |

| − | example, a working library could support coding

| |

| − | and a project support library could support test

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ing, while a master library could be used for fin

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ished products. An appropriate level of SCM con

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | trol (associated baseline and level of authority for

| |

| − | change) is associated with each library. Security,

| |

| − | in terms of access control and the backup facili

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ties, is a key aspect of library management.

| |

| − | The tool(s) used for each library must support

| |

| − | the SCM control needs for that library—both in

| |

| − | terms of controlling SCIs and controlling access

| |

| − | to the library. At the working library level, this is

| |

| − | a code management capability serving develop

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ers, maintainers, and SCM. It is focused on man

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | aging the versions of software items while sup

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | porting the activities of multiple developers. At

| |

| − | higher levels of control, access is more restricted

| |

| − | and SCM is the primary user.

| |

| − | These libraries are also an important source

| |

| − | of information for measurements of work and

| |

| − | progress.

| |

| − | 3.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Control

| |

| − | [2*, c9] [4*, c29s2]

| |

| − | Software configuration control is concerned

| |

| − | with managing changes during the software

| |

| − | life cycle. It covers the process for determining

| |

| − | what changes to make, the authority for approv

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ing certain changes, support for the implementa

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion of those changes, and the concept of formal

| |

| − | deviations from project requirements as well as

| |

| − | waivers of them. Information derived from these

| |

| − | activities is useful in measuring change traffic

| |

| − | and breakage as well as aspects of rework.

| |

| − | 3.1.

| |

| − | Requesting,

| |

| − | Evaluating,

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | Approving

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Changes

| |

| − | [2*, c9s2.4] [4*, c29s2]

| |

| − | The first step in managing changes to controlled

| |

| − | items is determining what changes to make. The

| |

| − | software change request process (see a typical

| |

| − | flow of a change request process in Figure 6.3)

| |

| − | provides formal procedures for submitting and

| |

| − | recording change requests, evaluating the poten

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tial cost and impact of a proposed change, and

| |

| − | accepting, modifying, deferring, or rejecting

| |

| − | the proposed change. A change request (CR) is

| |

| − | a request to expand or reduce the project scope;

| |

| − | modify policies, processes, plans, or procedures;

| |

| − | modify costs or budgets; or revise schedules

| |

| − | [1]. Requests for changes to software configura

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion items may be originated by anyone at any

| |

| − | point in the software life cycle and may include

| |

| − | a suggested solution and requested priority. One

| |

| − | source of a CR is the initiation of corrective

| |

| − | action in response to problem reports. Regardless

| |

| − | of the source, the type of change (for example,

| |

| − | defect or enhancement) is usually recorded on the

| |

| − | Software CR (SCR).

| |

| − | This provides an opportunity for tracking

| |

| − | defects and collecting change activity measure

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ments by change type. Once an SCR is received,

| |

| − | a technical evaluation (also known as an impact

| |

| − | analysis) is performed to determine the extent of

| |

| − | the modifications that would be necessary should

| |

| − | the change request be accepted. A good under

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | standing of the relationships among software

| |

| − | (and, possibly, hardware) items is important for

| |

| − | this task. Finally, an established authority—com

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mensurate with the affected baseline, the SCI

| |

| − | involved, and the nature of the change—will

| |

| − | evaluate the technical and managerial aspects

| |

| − | of the change request and either accept, modify,

| |

| − | reject, or defer the proposed change.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Management

| |

| − | 6-9

| |

| − | 3.1.1.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Control

| |

| − | Board

| |

| − | [2*, c9s2.2] [3*, c11s1] [4*, c29s2]

| |

| − | The authority for accepting or rejecting proposed

| |

| − | changes rests with an entity typically known as a

| |

| − | Configuration Control Board (CCB). In smaller

| |

| − | projects, this authority may actually reside with

| |

| − | the leader or an assigned individual rather than a

| |

| − | multiperson board. There can be multiple levels

| |

| − | of change authority depending on a variety of cri

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | teria—such as the criticality of the item involved,

| |

| − | the nature of the change (for example, impact on

| |

| − | budget and schedule), or the project’s current

| |

| − | point in the life cycle. The composition of the

| |

| − | CCBs used for a given system varies depending

| |

| − | on these criteria (an SCM representative would

| |

| − | always be present). All stakeholders, appropriate

| |

| − | to the level of the CCB, are represented. When

| |

| − | the scope of authority of a CCB is strictly soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware, it is known as a Software Configuration

| |

| − | Control Board (SCCB). The activities of the CCB

| |

| − | are typically subject to software quality audit or

| |

| − | review.

| |

| − | 3.1.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Change

| |

| − | Request

| |

| − | Process

| |

| − | [3*, c1s4, c8s4]

| |

| − | An effective software change request (SCR) pro

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cess requires the use of supporting tools and pro

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cedures for originating change requests, enforc

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ing the flow of the change process, capturing

| |

| − | CCB decisions, and reporting change process

| |

| − | information. A link between this tool capability

| |

| − | and the problem-reporting system can facilitate

| |

| − | the tracking of solutions for reported problems.

| |

| − | 3.2.

| |

| − | Implementing

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Changes

| |

| − | [4*, c29]

| |

| − | Approved SCRs are implemented using the

| |

| − | defined software procedures in accordance with

| |

| − | the applicable schedule requirements. Since a

| |

| − | number of approved SCRs might be implemented

| |

| − | simultaneously, it is necessary to provide a means

| |

| − | for tracking which SCRs are incorporated into

| |

| − | particular software versions and baselines. As

| |

| − | part of the closure of the change process, com

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | pleted changes may undergo configuration audits

| |

| − | and software quality verification—this includes

| |

| − | ensuring that only approved changes have been

| |

| − | made. The software change request process

| |

| − | described above will typically document the

| |

| − | SCM (and other) approval information for the

| |

| − | change.

| |

| − | Changes may be supported by source code ver

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sion control tools. These tools allow a team of

| |

| − | software engineers, or a single software engineer,

| |

| − | to track and document changes to the source code.

| |

| − | These tools provide a single repository for storing

| |

| − | the source code, can prevent more than one soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware engineer from editing the same module at

| |

| − | the same time, and record all changes made to the

| |

| − | Figure 6.3.

| |

| − | Flow of a Change Control Process

| |

| − | 6-10

| |

| − | SWEBOK® Guide

| |

| − | V3.0

| |

| − | source code. Software engineers check modules

| |

| − | out of the repository, make changes, document

| |

| − | the changes, and then save the edited modules

| |

| − | in the repository. If needed, changes can also be

| |

| − | discarded, restoring a previous baseline. More

| |

| − | powerful tools can support parallel development

| |

| − | and geographically distributed environments.

| |

| − | These tools may be manifested as separate,

| |

| − | specialized applications under the control of an

| |

| − | independent SCM group. They may also appear

| |

| − | as an integrated part of the software engineering

| |

| − | environment. Finally, they may be as elementary

| |

| − | as a rudimentary change control system provided

| |

| − | with an operating system.

| |

| − | 3.3.

| |

| − | Deviations

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | Waivers

| |

| − | [1, c3]

| |

| − | The constraints imposed on a software engineer

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ing effort or the specifications produced during the

| |

| − | development activities might contain provisions

| |

| − | that cannot be satisfied at the designated point

| |

| − | in the life cycle. A deviation is a written autho

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | rization, granted prior to the manufacture of an

| |

| − | item, to depart from a particular performance or

| |

| − | design requirement for a specific number of units

| |

| − | or a specific period of time. A waiver is a writ

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ten authorization to accept a configuration item or

| |

| − | other designated item that is found, during produc

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion or after having been submitted for inspection,

| |

| − | to depart from specified requirements but is nev

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ertheless considered suitable for use as-is or after

| |

| − | rework by an approved method. In these cases, a

| |

| − | formal process is used for gaining approval for

| |

| − | deviations from, or waivers of, the provisions.

| |

| − | 4.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Status Accounting

| |

| − | [2*, c10]

| |

| − | Software configuration status accounting (SCSA)

| |

| − | is an element of configuration management con

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sisting of the recording and reporting of informa

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion needed to manage a configuration effectively.

| |

| − | 4.1.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Status

| |

| − | Information

| |

| − | [2*, c10s2.1]

| |

| − | The SCSA activity designs and operates a sys

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tem for the capture and reporting of necessary

| |

| − | information as the life cycle proceeds. As in any

| |

| − | information system, the configuration status infor

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mation to be managed for the evolving configura

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tions must be identified, collected, and maintained.

| |

| − | Various information and measurements are needed

| |

| − | to support the SCM process and to meet the con

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | figuration status reporting needs of management,

| |

| − | software engineering, and other related activities.

| |

| − | The types of information available include the

| |

| − | approved configuration identification as well as

| |

| − | the identification and current implementation sta

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tus of changes, deviations, and waivers.

| |

| − | Some form of automated tool support is neces

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sary to accomplish the SCSA data collection and

| |

| − | reporting tasks; this could be a database capabil

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ity, a stand-alone tool, or a capability of a larger,

| |

| − | integrated tool environment.

| |

| − | 4.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Status

| |

| − | Reporting

| |

| − | [2*, c10s2.4] [3*, c1s5, c9s1, c17]

| |

| − | Reported information can be used by various

| |

| − | organizational and project elements—including

| |

| − | the development team, the maintenance team,

| |

| − | project management, and software quality activi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ties. Reporting can take the form of ad hoc que

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ries to answer specific questions or the periodic

| |

| − | production of predesigned reports. Some infor

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mation produced by the status accounting activity

| |

| − | during the course of the life cycle might become

| |

| − | quality assurance records.

| |

| − | In addition to reporting the current status of the

| |

| − | configuration, the information obtained by the

| |

| − | SCSA can serve as a basis of various measure

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ments. Examples include the number of change

| |

| − | requests per SCI and the average time needed to

| |

| − | implement a change request.

| |

| − | 5.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Auditing

| |

| − | [2*, c11]

| |

| − | A software audit is an independent examina

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion of a work product or set of work products to

| |

| − | assess compliance with specifications, standards,

| |

| − | contractual agreements, or other criteria [1].

| |

| − | Audits are conducted according to a well-defined

| |

| − | process consisting of various auditor roles and

| |

| − | responsibilities. Consequently, each audit must

| |

| − | be carefully planned. An audit can require a num

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ber of individuals to perform a variety of tasks

| |

| − | over a fairly short period of time. Tools to support

| |

| − | Software Configuration Management

| |

| − | 6-11

| |

| − | the planning and conduct of an audit can greatly

| |

| − | facilitate the process.

| |

| − | Software configuration auditing determines

| |

| − | the extent to which an item satisfies the required

| |

| − | functional and physical characteristics. Informal

| |

| − | audits of this type can be conducted at key points

| |

| − | in the life cycle. Two types of formal audits might

| |

| − | be required by the governing contract (for exam

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ple, in contracts covering critical software): the

| |

| − | Functional Configuration Audit (FCA) and the

| |

| − | Physical Configuration Audit (PCA). Successful

| |

| − | completion of these audits can be a prerequisite

| |

| − | for the establishment of the product baseline.

| |

| − | 5.1.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Functional

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Audit

| |

| − | [2*, c11s2.1]

| |

| − | The purpose of the software FCA is to ensure that

| |

| − | the audited software item is consistent with its

| |

| − | governing specifications. The output of the soft

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ware verification and validation activities (see

| |

| − | Verification and Validation in the Software Qual

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ity KA) is a key input to this audit.

| |

| − | 5.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Physical

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Audit

| |

| − | [2*, c11s2.2]

| |

| − | The purpose of the software physical configura

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion audit (PCA) is to ensure that the design and

| |

| − | reference documentation is consistent with the

| |

| − | as-built software product.

| |

| − | 5.3.

| |

| − | In-Process

| |

| − | Audits

| |

| − | of

| |

| − | a

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Baseline

| |

| − | [2*, c11s2.3]

| |

| − | As mentioned above, audits can be carried out

| |

| − | during the development process to investigate

| |

| − | the current status of specific elements of the con

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | figuration. In this case, an audit could be applied

| |

| − | to sampled baseline items to ensure that per

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | formance is consistent with specifications or to

| |

| − | ensure that evolving documentation continues to

| |

| − | be consistent with the developing baseline item.

| |

| − | 6.

| |

| − | Software Release Management and

| |

| − | Delivery

| |

| − | [2*, c14] [3*, c8s2]

| |

| − | In this context,

| |

| − | release

| |

| − | refers to the distribu

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tion of a software configuration item outside

| |

| − | the development activity; this includes internal

| |

| − | releases as well as distribution to customers. When

| |

| − | different versions of a software item are available

| |

| − | for delivery (such as versions for different plat

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | forms or versions with varying capabilities), it is

| |

| − | frequently necessary to recreate specific versions

| |

| − | and package the correct materials for delivery of

| |

| − | the version. The software library is a key element

| |

| − | in accomplishing release and delivery tasks.

| |

| − | 6.1.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Building

| |

| − | [4*, c29s4]

| |

| − | Software building is the activity of combining the

| |

| − | correct versions of software configuration items,

| |

| − | using the appropriate configuration data, into an

| |

| − | executable program for delivery to a customer or

| |

| − | other recipient, such as the testing activity. For

| |

| − | systems with hardware or firmware, the executable

| |

| − | program is delivered to the system-building activ

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ity. Build instructions ensure that the proper build

| |

| − | steps are taken in the correct sequence. In addition

| |

| − | to building software for new releases, it is usually

| |

| − | also necessary for SCM to have the capability to

| |

| − | reproduce previous releases for recovery, testing,

| |

| − | maintenance, or additional release purposes.

| |

| − | Software is built using particular versions of

| |

| − | supporting tools, such as compilers (see Com

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | piler Basics in the Computing Foundations KA).

| |

| − | It might be necessary to rebuild an exact copy of

| |

| − | a previously built software configuration item. In

| |

| − | this case, supporting tools and associated build

| |

| − | instructions need to be under SCM control to

| |

| − | ensure availability of the correct versions of the

| |

| − | tools.

| |

| − | A tool capability is useful for selecting the cor

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | rect versions of software items for a given target

| |

| − | environment and for automating the process of

| |

| − | building the software from the selected versions

| |

| − | and appropriate configuration data. For projects

| |

| − | with parallel or distributed development envi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ronments, this tool capability is necessary. Most

| |

| − | software engineering environments provide this

| |

| − | capability. These tools vary in complexity from

| |

| − | requiring the software engineer to learn a spe

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cialized scripting language to graphics-oriented

| |

| − | approaches that hide much of the complexity of

| |

| − | an “intelligent” build facility.

| |

| − | The build process and products are often sub

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ject to software quality verification. Outputs of

| |

| − | 6-12

| |

| − | SWEBOK® Guide

| |

| − | V3.0

| |

| − | the build process might be needed for future refer

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ence and may become quality assurance records.

| |

| − | 6.2.

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Release

| |

| − | Management

| |

| − | [4*, c29s3.2]

| |

| − | Software release management encompasses the

| |

| − | identification, packaging, and delivery of the

| |

| − | elements of a product—for example, an execut

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | able program, documentation, release notes, and

| |

| − | configuration data. Given that product changes

| |

| − | can occur on a continuing basis, one concern for

| |

| − | release management is determining when to issue

| |

| − | a release. The severity of the problems addressed

| |

| − | by the release and measurements of the fault den

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | sities of prior releases affect this decision. The

| |

| − | packaging task must identify which product items

| |

| − | are to be delivered and then select the correct

| |

| − | variants of those items, given the intended appli

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cation of the product. The information document

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ing the physical contents of a release is known

| |

| − | as a version description document

| |

| − | .

| |

| − | The release

| |

| − | notes typically describe new capabilities, known

| |

| − | problems, and platform requirements necessary

| |

| − | for proper product operation. The package to be

| |

| − | released also contains installation or upgrading

| |

| − | instructions. The latter can be complicated by the

| |

| − | fact that some current users might have versions

| |

| − | that are several releases old. In some cases, release

| |

| − | management might be required in order to track

| |

| − | distribution of the product to various customers

| |

| − | or target systems—for example, in a case where

| |

| − | the supplier was required to notify a customer of

| |

| − | newly reported problems. Finally, a mechanism

| |

| − | to ensure the integrity of the released item can be

| |

| − | implemented—for example by releasing a digital

| |

| − | signature with it.

| |

| − | A tool capability is needed for supporting

| |

| − | these release management functions. It is use

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ful to have a connection with the tool capability

| |

| − | supporting the change request process in order to

| |

| − | map release contents to the SCRs that have been

| |

| − | received. This tool capability might also maintain

| |

| − | information on various target platforms and on

| |

| − | various customer environments.

| |

| − | 7.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Management Tools

| |

| − | [3*, c26s1] [4*, c8s2]

| |

| − | When discussing software configuration manage

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ment tools, it is helpful to classify them. SCM

| |

| − | tools can be divided into three classes in terms

| |

| − | of the scope at which they provide support: indi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | vidual support, project-related support, and com

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | panywide-process support.

| |

| − | Individual

| |

| − | support

| |

| − | tools

| |

| − | are appropriate and

| |

| − | typically sufficient for small organizations or

| |

| − | development groups without variants of their

| |

| − | software products or other complex SCM require

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ments. They include:

| |

| − | •

| |

| − | Version control tools: track, document, and

| |

| − | store individual configuration items such as

| |

| − | source code and external documentation.

| |

| − | •

| |

| − | Build handling tools: in their simplest form,

| |

| − | such tools compile and link an executable

| |

| − | version of the software. More advanced

| |

| − | building tools extract the latest version from

| |

| − | the version control software, perform qual

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ity checks, run regression tests, and produce

| |

| − | various forms of reports, among other tasks.

| |

| − | •

| |

| − | Change control tools: mainly support the

| |

| − | control of change requests and events noti

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | fication (for example, change request status

| |

| − | changes, milestones reached).

| |

| − | Project-related

| |

| − | support

| |

| − | tools

| |

| − | mainly support

| |

| − | workspace management for development teams

| |

| − | and integrators; they are typically able to sup

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | port distributed development environments. Such

| |

| − | tools are appropriate for medium to large organi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | zations with variants of their software products

| |

| − | and parallel development but no certification

| |

| − | requirements.

| |

| − | Companywide-process

| |

| − | support

| |

| − | tools

| |

| − | can typi

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cally automate portions of a companywide pro

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | cess, providing support for workflow manage

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | ments, roles, and responsibilities. They are able

| |

| − | to handle many items, data, and life cycles. Such

| |

| − | tools add to project-related support by supporting

| |

| − | a more formal development process, including

| |

| − | certification requirements.

| |

| − | Software Configuration Management

| |

| − | 6-15

| |

| − | FURTHER READINGS

| |

| − | Stephen P. Berczuk and Brad Appleton,

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Management

| |

| − | Patterns:

| |

| − | Effective

| |

| − | Teamwork,

| |

| − | Practical

| |

| − | Integration

| |

| − | [6].

| |

| − | This book expresses useful SCM practices and

| |

| − | strategies as patterns. The patterns can be imple

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | mented using various tools, but they are expressed

| |

| − | in a tool-agnostic fashion.

| |

| − | “CMMI for Development,” Version 1.3, pp.

| |

| − | 137–147 [7].

| |

| − | This model presents a collection of best prac

| |

| − | -

| |

| − | tices to help software development organizations

| |

| − | improve their processes. At maturity level 2, it

| |

| − | suggests configuration management activities.

| |

| − | REFERENCES

| |

| − | [1]

| |

| − | ISO/IEC/IEEE

| |

| − | 24765:2010

| |

| − | Systems

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Engineering—Vocabulary

| |

| − | , ISO/

| |

| − | IEC/IEEE, 2010.

| |

| − | [2*]

| |

| − | IEEE

| |

| − | Std.

| |

| − | 828-2012,

| |

| − | Standard

| |

| − | for

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Management

| |

| − | in

| |

| − | Systems

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Engineering

| |

| − | , IEEE, 2012.

| |

| − | [3*] A.M.J. Hass,

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Management

| |

| − | Principles

| |

| − | and

| |

| − | Practices

| |

| − | , 1st ed., Addison-

| |

| − | Wesley, 2003.

| |

| − | [4*] I. Sommerville,

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Engineering

| |

| − | , 9th

| |

| − | ed., Addison-Wesley, 2011.

| |

| − | [5*] J.W. Moore,

| |

| − | The

| |

| − | Road

| |

| − | Map

| |

| − | to

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Engineering:

| |

| − | A

| |

| − | Standards-Based

| |

| − | Guide

| |

| − | ,

| |

| − | Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press, 2006.

| |

| − | [6] S.P. Berczuk and B. Appleton,

| |

| − | Software

| |

| − | Configuration

| |

| − | Management

| |

| − | Patterns:

| |

| − | Effective

| |

| − | Teamwork,

| |

| − | Practical

| |

| − | Integration

| |

| − | ,

| |

| − | Addison-Wesley Professional, 2003.

| |

| − | [7] CMMI Product Team, “CMMI for

| |

| − | Development, Version 1.3,” Software

| |

| − | Engineering Institute, 2010;

| |

| − | http://

| |

| − | resources.sei.cmu.edu/library/asset-view.

| |

| − | cfm?assetID=9661

| |

A system can be defined as the combination of interacting elements organized to achieve one or more stated purposes [1]. The configuration of a system is the functional and physical characteristics of hardware or software as set forth in technical documentation or achieved in a product [1]; it can also be thought of as a collection of specific versions of hardware, firmware, or software items combined according to specific build procedures to serve a particular purpose. Configuration management (CM), then, is the discipline of identifying the configuration of a system at distinct points in time for the purpose of systematically controlling changes to the configuration and maintaining the integrity and traceability of the configuration throughout the system life cycle. It is formally

defined as

A discipline applying technical and administrative direction and surveillance to: identify and document the functional and physical characteristics of a configuration item, control changes to those characteristics, record and report change processing and implementation status, and verify compliance with specified requirements. [1]

Software configuration management (SCM) is a supporting-software life cycle process that benefits project management, development and maintenance activities, quality assurance activities, as well as the customers and users of the end product. The concepts of configuration management apply to all items to be controlled, although there are some differences in implementation between hardware CM and software CM. SCM is closely related to the software quality assurance (SQA) activity. As defined in the Software Quality knowledge area (KA), SQA processes provide assurance that the software products and processes in the project life cycle

conform to their specified requirements by planning, enacting, and performing a set of activities to provide adequate confidence that quality is being built into the software. SCM activities help in accomplishing these SQA goals. In some project contexts, specific SQA requirements prescribe certain SCM activities.

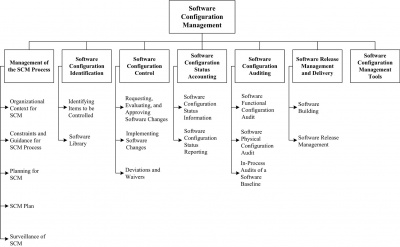

The SCM activities are management and planning of the SCM process, software configuration identification, software configuration control, software configuration status accounting, software configuration auditing, and software release management and delivery. The Software Configuration Management KA is related to all the other KAs, since the object of configuration management is the artifact produced and used throughout the software engineering process.

The breakdown of topics for the Software Configuration Management KA is shown in Figure 6.1.

SCM controls the evolution and integrity of a product by identifying its elements; managing and controlling change; and verifying, recording, and reporting on configuration information. From the software engineer’s perspective, SCM facilitates development and change implementation activities. A successful SCM implementation requires careful planning and management. This, in turn, requires an understanding of the organizational context for, and the constraints placed on, the design and implementation of the SCM process.

To plan an SCM process for a project, it is necessary to understand the organizational context and the relationships among organizational elements. SCM interacts with several other activities or organizational elements. The organizational elements responsible for the software engineering supporting processes may be structured in various ways. Although the responsibility for performing certain SCM tasks might be assigned to other parts of the organization (such as the development organization), the overall responsibility for SCM often rests with a distinct organizational element or designated individual. Software is frequently developed as part of a larger system containing hardware and firmware elements. In this case, SCM activities take place in parallel with hardware and firmware CM activities and must be consistent with system-level CM. Note that firmware contains hardware and software; therefore, both hardware and software CM concepts are applicable. SCM might interface with an organization’s quality assurance activity on issues such as records management and nonconforming items. Regarding the former, some items under SCM control might also be project records subject to provisions of the organization’s quality assurance program. Managing nonconforming items is usually the responsibility of the quality assurance activity; however, SCM might assist with tracking and reporting on software configuration items falling into this category. Perhaps the closest relationship is with the software development and maintenance organizations. It is within this context that many of the software configuration control tasks are conducted. Frequently, the same tools support development, maintenance, and SCM purposes.

Constraints affecting, and guidance for, the SCM

process come from a number of sources. Policies

and procedures set forth at corporate or other

organizational levels might influence or prescribe

the design and implementation of the SCM process

for a given project. In addition, the contract

between the acquirer and the supplier might contain

provisions affecting the SCM process. For

example, certain configuration audits might be

required, or it might be specified that certain items

be placed under CM. When software products to

be developed have the potential to affect public

safety, external regulatory bodies may impose

constraints. Finally, the particular software life

cycle process chosen for a software project and

the level of formalism selected to implement the

software affect the design and implementation of

the SCM process. Guidance for designing and implementing an

SCM process can also be obtained from “best

practice,” as reflected in the standards on software engineering issued by the various standards organizations

(see Appendix B on standards).

The planning of an SCM process for a given

project should be consistent with the organizational

context, applicable constraints, commonly

accepted guidance, and the nature of the

project (for example, size, safety criticality, and

security). The major activities covered are software

configuration identification, software configuration

control, software configuration status

accounting, software configuration auditing, and

software release management and delivery. In

addition, issues such as organization and responsibilities,

resources and schedules, tool selection

and implementation, vendor and subcontractor

control, and interface control are typically considered.

The results of the planning activity are

recorded in an SCM Plan (SCMP), which is typically

subject to SQA review and audit.

Branching and merging strategies should be

carefully planned and communicated, since they

impact many SCM activities. From an SCM standpoint,

a branch is defined as a set of evolving source

file versions [1]. Merging consists in combining

different changes to the same file [1]. This typically

occurs when more than one person changes a

configuration item. There are many branching and

merging strategies in common use (see the Further

Readings section for additional discussion).

The software development life cycle model

(see Software Life Cycle Models in the Software

Engineering Process KA) also impacts SCM

activities, and SCM planning should take this

into account. For instance, continuous integration

is a common practice in many software development

approaches. It is typically characterized by

frequent build-test-deploy cycles. SCM activities

must be planned accordingly.

To prevent confusion about who will perform

given SCM activities or tasks, organizational roles to be involved in the SCM process need

to be clearly identified. Specific responsibilities

for given SCM activities or tasks also need to be

assigned to organizational entities, either by title

or by organizational element. The overall authority

and reporting channels for SCM should also be

identified, although this might be accomplished

at the project management or quality assurance

planning stage.

Planning for SCM identifies the staff and tools

involved in carrying out SCM activities and tasks.

It addresses scheduling questions by establishing

necessary sequences of SCM tasks and identifying

their relationships to the project schedules

and milestones established at the project management

planning stage. Any training requirements

necessary for implementing the plans and training

new staff members are also specified.

As for any area of software engineering, the

selection and implementation of SCM tools

should be carefully planned. The following questions

should be considered:

SCM typically requires a set of tools, as

opposed to a single tool. Such tool sets are sometimes

referred to as workbenches. In such a context,

another important consideration in planning

for tool selection is determining if the SCM

workbench will be open (in other words, tools

from different suppliers will be used in different

activities of the SCM process) or integrated

(where elements of the workbench are designed

to work together).

The size of the organization and the type of

projects involved may also impact tool selection

(see topic 7, Software Configuration Management

Tools).

A software project might acquire or make use of

purchased software products, such as compilers

or other tools. SCM planning considers if and

how these items will be taken under configuration

control (for example, integrated into the project

libraries) and how changes or updates will be

evaluated and managed.

Similar considerations apply to subcontracted

software. When using subcontracted software,

both the SCM requirements to be imposed on

the subcontractor’s SCM process as part of the

subcontract and the means for monitoring compliance

need to be established. The latter includes

consideration of what SCM information must be

available for effective compliance monitoring.

When a software item will interface with

another software or hardware item, a change

to either item can affect the other. Planning for

the SCM process considers how the interfacing

items will be identified and how changes to the

items will be managed and communicated. The

SCM role may be part of a larger, system-level

process for interface specification and control;

it may involve interface specifications, interface

control plans, and interface control documents.

In this case, SCM planning for interface control

takes place within the context of the systemlevel

process.

The results of SCM planning for a given project

are recorded in a software configuration management

plan (SCMP), a “living document” which

serves as a reference for the SCM process. It is

maintained (that is, updated and approved) as

necessary during the software life cycle. In implementing

the SCMP, it is typically necessary to

develop a number of more detailed, subordinate

procedures defining how specific requirements

will be carried out during day-to-day activities—

for example, which branching strategies will be

used and how frequently builds occur and automated

tests of all kinds are run.

Guidance on the creation and maintenance of

an SCMP, based on the information produced by

the planning activity, is available from a number

of sources, such as [2*]. This reference provides

requirements for the information to be contained

in an SCMP; it also defines and describes six categories

of SCM information to be included in an

SCMP:

After the SCM process has been implemented,

some degree of surveillance may be necessary

to ensure that the provisions of the SCMP are

properly carried out. There are likely to be specific

SQA requirements for ensuring compliance

with specified SCM processes and procedures.

The person responsible for SCM ensures that

those with the assigned responsibility perform

the defined SCM tasks correctly. The software

quality assurance authority, as part of a compliance

auditing activity, might also perform this

surveillance.

The use of integrated SCM tools with process

control capability can make the surveillance

task easier. Some tools facilitate process compliance

while providing flexibility for the software

engineer to adapt procedures. Other tools

enforce process, leaving the software engineer

with less flexibility. Surveillance requirements

and the level of flexibility to be provided to the

software engineer are important considerations

in tool selection.

SCM measures can be designed to provide specific

information on the evolving product or to

provide insight into the functioning of the SCM

process. A related goal of monitoring the SCM

process is to discover opportunities for process

improvement. Measurements of SCM processes

provide a good means for monitoring the effectiveness

of SCM activities on an ongoing basis.

These measurements are useful in characterizing

the current state of the process as well as in

providing a basis for making comparisons over

time. Analysis of the measurements may produce insights leading to process changes and corresponding

updates to the SCMP.

Software libraries and the various SCM tool

capabilities provide sources for extracting information

about the characteristics of the SCM

process (as well as providing project and management

information). For example, information

about the time required to accomplish various

types of changes would be useful in an evaluation

of the criteria for determining what levels of

authority are optimal for authorizing certain types

of changes and for estimating future changes.Care must be taken to keep the focus of the

surveillance on the insights that can be gained

from the measurements, not on the measurements

themselves. Discussion of software process and

product measurement is presented in the Software

Engineering Process KA. Software measurement

programs are described in the Software

Engineering Management KA.

Audits can be carried out during the software

engineering process to investigate the current status

of specific elements of the configuration or to

assess the implementation of the SCM process.

In-process auditing of SCM provides a more formal

mechanism for monitoring selected aspects

of the process and may be coordinated with the

SQA function (see topic 5, Software Configuration

Auditing).