Chapter 12: Software Engineering Economics

Contents

- 1 Software Engineering Economics Fundamentals

- 2 Life Cycle Economics

- 2.1 Product

- 2.2 Project

- 2.3 Program

- 2.4 Portfolio

- 2.5 Product Life Cycle

- 2.6 Project Life Cycle

- 2.7 Proposals

- 2.8 Investment Decisions

- 2.9 Planning Horizon

- 2.10 Price and Pricing

- 2.11 Cost and Costing

- 2.12 Performance Measurement

- 2.13 Earned Value Management

- 2.14 Termination Decisions

- 2.15 Replacement and Retirement Decisions

- 3 Risk and Uncertainty

- 4 Economic Analysis Methods

- 5 Practical Considerations

- EVM

- Earned Value Management

- IRR

- Internal Rate of Return

- MARR

- Minimum Acceptable Rate of Return

- SDLC

- Software Development Life Cycle

- SPLC

- Software Product Life Cycle

- ROI

- Return on Investment

- ROCE

- Return on Capital Employed

- TCO

- Total Cost of Ownership

Software engineering economics is about making decisions related to software engineering in a business context. The success of a software product, service, and solution depends on good business management. Yet, in many companies and organizations, software business relationships to software development and engineering remain vague. This knowledge area (KA) provides an overview on software engineering economics. Economics is the study of value, costs, resources, and their relationship in a given context or situation. In the discipline of software engineering, activities have costs, but the resulting software itself has economic attributes as well. Software engineering economics provides a way to study the attributes of software and software processes in a systematic way that relates them to economic measures. These economic measures can be weighed and analyzed when making decisions that are within the scope of a software organization and those within the integrated scope of an entire producing or acquiring business. Software engineering economics is concerned with aligning software technical decisions with the business goals of the organization. In all types of organizations — be it “for-profit,” “notfor- profit,” or governmental — this translates into sustainably staying in business. In “for-profit” organizations this additionally relates to achieving a tangible return on the invested capital — both assets and capital employed. This KA has been formulated in a way to address all types of organizations independent of focus, product and service portfolio, or capital ownership and taxation restrictions. Decisions like “Should we use a specific component?” may look easy from a technical perspective, but can have serious implications on the business viability of a software project and the resulting product. Often engineers wonder whether such concerns apply at all, as they are “only engineers.” Economic analysis and decision-making are important engineering considerations because engineers are capable of evaluating decisions both technically and from a business perspective. The contents of this knowledge area are important topics for software engineers to be aware of even if they are never actually involved in concrete business decisions; they will have a well-rounded view of business issues and the role technical considerations play in making business decisions. Many engineering proposals and decisions, such as make versus buy, have deep intrinsic economic impacts that should be considered explicitly. This KA first covers the foundations, key terminology, basic concepts, and common practices of software engineering economics to indicate how decision-making in software engineering includes, or should include a business perspective. It then provides a life cycle perspective, highlights risk and uncertainty management, and shows how economic analysis methods are used. Some practical considerations finalize the knowledge area.

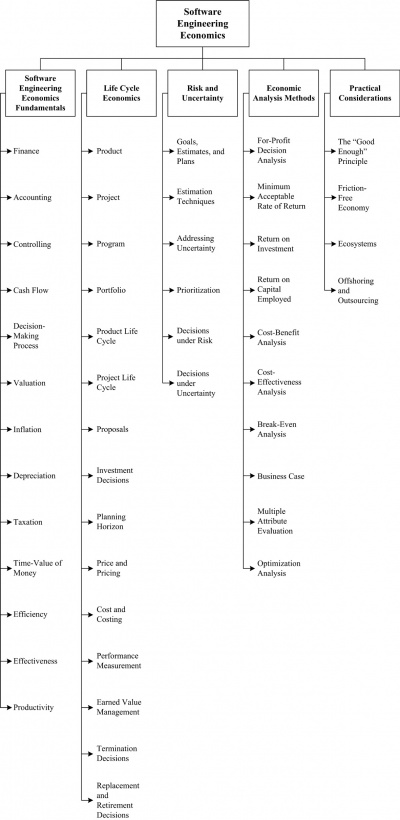

The breakdown of topics for the Software Engineering Economics KA is shown in Figure 12.1.

1 Software Engineering Economics Fundamentals

1.1 Finance

Finance is the branch of economics concerned with issues such as allocation, management, acquisition, and investment of resources. Finance is an element of every organization, including software engineering organizations. The field of finance deals with the concepts of time, money, risk, and how they are interrelated. It also deals with how money is spent and budgeted. Corporate finance is concerned with providing the funds for an organization’s activities. Generally, this involves balancing risk and profitability, while attempting to maximize an organization’s wealth and the value of its stock. This holds primarily for “for-profit” organizations, but also applies to “not-for-profit” organizations. The latter needs finances to ensure sustainability, while not targeting tangible profit. To do this, an organization must

- identify organizational goals, time horizons, risk factors, tax considerations, and financial constraints;

- identify and implement the appropriate business strategy, such as which portfolio and investment decisions to take, how to manage cash flow, and where to get the funding;

- measure financial performance, such as cash flow and ROI (see section 4.3, Return on Investment), and take corrective actions in case of deviation from objectives and strategy.

1.2 Accounting

Accounting is part of finance. It allows people whose money is being used to run an organization to know the results of their investment: did they get the profit they were expecting? In “for-profit” organizations, this relates to the tangible ROI (see section 4.3, Return on Investment), while in “not-for-profit” and governmental organizations as well as “for-profit” organizations, it translates into sustainably staying in business. The primary role of accounting is to measure the organization’s actual financial performance and to communicate financial information about a business entity to stakeholders, such as shareholders, financial auditors, and investors. Communication is generally in the form of financial statements that show in money terms the economic resources to be controlled. It is important to select the right information that is both relevant and reliable to the user. Information and its timing are partially governed by risk management and governance policies. Accounting systems are also a rich source of historical data for estimating.

1.3 Controlling

Controlling is an element of finance and accounting. Controlling involves measuring and correcting the performance of finance and accounting. It ensures that an organization’s objectives and plans are accomplished. Controlling cost is a specialized branch of controlling used to detect variances of actual costs from planned costs.

1.4 Cash Flow

Cash flow is the movement of money into or out of a business, project, or financial product over a given period. The concepts of cash flow instances and cash flow streams are used to describe the business perspective of a proposal. To make a meaningful business decision about any specific proposal, that proposal will need to be evaluated from a business perspective. In a proposal to develop and launch product X, the payment for new software licenses is an example of an outgoing cash flow instance. Money would need to be spent to carry out that proposal. The sales income from product X in the 11th month after market launch is an example of an incoming cash flow instance. Money would be coming in because of carrying out the proposal.

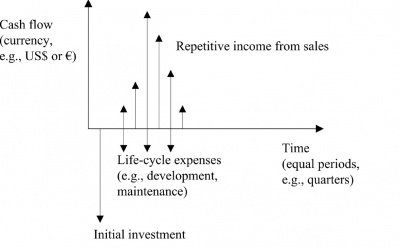

The term cash flow stream refers to the set of cash flow instances over time that are caused by carrying out some given proposal. The cash flow stream is, in effect, the complete financial picture of that proposal. How much money goes out? When does it go out? How much money comes in? When does it come in? Simply, if the cash flow stream for Proposal A is more desirable than the cash flow stream for Proposal B, then—all other things being equal—the organization is better off carrying out Proposal A than Proposal B. Thus, the cash flow stream is an important input for investment decision-making. A cash flow instance is a specific amount of money flowing into or out of the organization at a specific time as a direct result of some activity. A cash flow diagram is a picture of a cash flow stream. It gives the reader a quick overview of the financial picture of the subject organization or project. Figure 12.2 shows an example of a cash flow diagram for a proposal.

1.5 Decision-Making Process

If we assume that candidate solutions solve a given technical problem equally well, why should the organization care which one is chosen? The answer is that there is usually a large difference in the costs and incomes from the different solutions. A commercial, off-the-shelf, objectrequest broker product might cost a few thousand dollars, but the effort to develop a homegrown service that gives the same functionality could easily cost several hundred times that amount.

If the candidate solutions all adequately solve the problem from a technical perspective, then the selection of the most appropriate alternative should be based on commercial factors such as optimizing total cost of ownership (TCO) or maximizing the short-term return on investment (ROI). Life cycle costs such as defect correction, field service, and support duration are also relevant considerations. These costs need to be factored in when selecting among acceptable technical approaches, as they are part of the lifetime ROI (see section 4.3, Return on Investment). A systematic process for making decisions will achieve transparency and allow later justification. Governance criteria in many organizations demand selection from at least two alternatives.

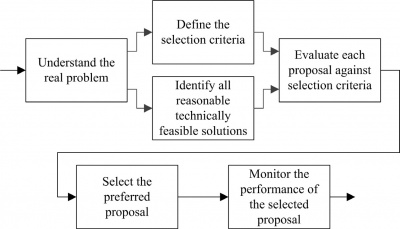

A systematic process is shown in Figure 12.3. It starts with a business challenge at hand and describes the steps to identify alternative solutions, define selection criteria, evaluate the solutions, implement one selected solution, and monitor the performance of that solution.

Figure 12.3 shows the process as mostly stepwise and serial. The real process is more fluid. Sometimes the steps can be done in a different order and often several of the steps can be done in parallel. The important thing is to be sure that none of the steps are skipped or curtailed. It’s also important to understand that this same process applies at all levels of decision making: from a decision as big as determining whether a software project should be done at all, to a deciding on an algorithm or data structure to use in a software module. The difference is how financially significant the decision is and, therefore, how much effort should be invested in making that decision. The project-level decision is financially significant and probably warrants a relatively high level of effort to make the decision. Selecting an algorithm is often much less financially significant and warrants a much lower level of effort to make the decision, even though the same basic decision-making process is being used.

More often than not, an organization could carry out more than one proposal if it wanted to, and usually there are important relationships among proposals. Maybe Proposal Y can only be carried out if Proposal X is also carried out. Or maybe Proposal P cannot be carried out if Proposal Q is carried out, nor could Q be carried out if P were. Choices are much easier to make when there are mutually exclusive paths—for example, either A or B or C or whatever is chosen. In preparing decisions, it is recommended to turn any given set of proposals, along with their various interrelationships, into a set of mutually exclusive alternatives. The choice can then be made among these alternatives.

1.6 Valuation

In an abstract sense, the decision-making process— be it financial decision making or other— is about maximizing value. The alternative that maximizes total value should always be chosen. A financial basis for value-based comparison is comparing two or more cash flows. Several bases of comparison are available, including

- present worth

- future worth

- annual equivalent

- internal rate of return

- (discounted) payback period.

Based on the time-value of money, two or more cash flows are equivalent only when they equal the same amount of money at a common point in time. Comparing cash flows only makes sense when they are expressed in the same time frame.

Note that value can’t always be expressed in terms of money. For example, whether an item is a brand name or not can significantly affect its perceived value. Relevant values that can’t be expressed in terms of money still need to be expressed in similar terms so that they can be evaluated objectively.

1.7 Inflation

Inflation describes long-term trends in prices. Inflation means that the same things cost more than they did before. If the planning horizon of a business decision is longer than a few years, or if the inflation rate is over a couple of percentage points annually, it can cause noticeable changes in the value of a proposal. The present time value therefore needs to be adjusted for inflation rates and also for exchange rate fluctuations.

1.8 Depreciation

Depreciation involves spreading the cost of a tangible asset across a number of time periods; it is used to determine how investments in capitalized assets are charged against income over several years. Depreciation is an important part of determining after-tax cash flow, which is critical for accurately addressing profit and taxes. If a software product is to be sold after the development costs are incurred, those costs should be capitalized and depreciated over subsequent time periods. The depreciation expense for each time period is the capitalized cost of developing the software divided across the number of periods in which the software will be sold. A software project proposal may be compared to other software and nonsoftware proposals or to alternative investment options, so it is important to determine how those other proposals would be depreciated and how profits would be estimated.

1.9 Taxation

Governments charge taxes in order to finance expenses that society needs but that no single organization would invest in. Companies have to pay income taxes, which can take a substantial portion of a corporation’s gross profit. A decision analysis that does not account for taxation can lead to the wrong choice. A proposal with a high pretax profit won’t look nearly as profitable in posttax terms. Not accounting for taxation can also lead to unrealistically high expectations about how profitable a proposed product might be.

1.10 Time-Value of Money

One of the most fundamental concepts in finance—and therefore, in business decisions— is that money has time-value: its value changes over time. A specific amount of money right now almost always has a different value than the same amount of money at some other time. This concept has been around since the earliest recorded human history and is commonly known as time-value. In order to compare proposals or portfolio elements, they should be normalized in cost, value, and risk to the net present value. Currency exchange variations over time need to be taken into account based on historical data. This is particularly important in cross-border developments of all kinds.

1.11 Efficiency

Economic efficiency of a process, activity, or task is the ratio of resources actually consumed to resources expected to be consumed or desired to be consumed in accomplishing the process, activity, or task. Efficiency means “doing things right.” An efficient behavior, like an effective behavior, delivers results—but keeps the necessary effort to a minimum. Factors that may affect efficiency in software engineering include product complexity, quality requirements, time pressure, process capability, team distribution, interrupts, feature churn, tools, and programming language.

1.12 Effectiveness

Effectiveness is about having impact. It is the relationship between achieved objectives to defined objectives. Effectiveness means “doing the right things.” Effectiveness looks only at whether defined objectives are reached—not at how they are reached.

1.13 Productivity

Productivity is the ratio of output over input from an economic perspective. Output is the value delivered. Input covers all resources (e.g., effort) spent to generate the output. Productivity combines efficiency and effectiveness from a valueoriented perspective: maximizing productivity is about generating highest value with lowest resource consumption.

2 Life Cycle Economics

2.1 Product

A product is an economic good (or output) that is created in a process that transforms product factors (or inputs) to an output. When sold, a product is a deliverable that creates both a value and an experience for its users. A product can be a combination of systems, solutions, materials, and services delivered internally (e.g., in-house IT solution) or externally (e.g., software application), either as-is or as a component for another product (e.g., embedded software).

2.2 Project

A project is “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result”. In software engineering, different project types are distinguished (e.g., product development, outsourced services, software maintenance, service creation, and so on). During its life cycle, a software product may require many projects. For example, during the product conception phase, a project might be conducted to determine the customer need and market requirements; during maintenance, a project might be conducted to produce a next version of a product.

2.3 Program

A program is “a group of related projects, subprograms, and program activities managed in a coordinated way to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually.” Programs are often used to identify and manage different deliveries to a single customer or market over a time horizon of several years.

2.4 Portfolio

Portfolios are “projects, programs, subportfolios, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives.” Portfolios are used to group and then manage simultaneously all assets within a business line or organization. Looking to an entire portfolio makes sure that impacts of decisions are considered, such as resource allocation to a specific project—which means that the same resources are not available for other projects.

2.5 Product Life Cycle

A software product life cycle (SPLC) includes all activities needed to define, build, operate, maintain, and retire a software product or service and its variants. The SPLC activities of “operate,” “maintain,” and “retire” typically occur in a much longer time frame than initial software development (the software development life cycle—SDLC—see Software Life Cycle Models in the Software Engineering Process KA). Also the operate-maintain-retire activities of an SPLC typically consume more total effort and other resources than the SDLC activities (see Majority of Maintenance Costs in the Software Maintenance KA). The value contributed by a software product or associated services can be objectively determined during the “operate and maintain” time frame. Software engineering economics should be concerned with all SPLC activities, including the activities after initial product release.

2.6 Project Life Cycle

Project life cycle activities typically involve five process groups—Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing [4] (see the Software Engineering Management KA). The activities within a software project life cycle are often interleaved, overlapped, and iterated in various ways [3*, c2] [5] (see the Software Engineering Process KA). For instance, agile product development within an SPLC involves multiple iterations that produce increments of deliverable software. An SPLC should include risk management and synchronization with different suppliers (if any), while providing auditable decision-making information (e.g., complying with product liability needs or governance regulations). The software project life cycle and the software product life cycle are interrelated; an SPLC may include several SDLCs.

2.7 Proposals

Making a business decision begins with the notion of a proposal. Proposals relate to reaching a business objective—at the project, product, or portfolio level. A proposal is a single, separate option that is being considered, like carrying out a particular software development project or not. Another proposal could be to enhance an existing software component, and still another might be to redevelop that same software from scratch. Each proposal represents a unit of choice—either you can choose to carry out that proposal or you can choose not to. The whole purpose of business decision-making is to figure out, given the current business circumstances, which proposals should be carried out and which shouldn’t.

2.8 Investment Decisions

Investors make investment decisions to spend money and resources on achieving a target objective. Investors are either inside (e.g., finance, board) or outside (e.g., banks) the organization. The target relates to some economic criteria, such as achieving a high return on the investment, strengthening the capabilities of the organization, or improving the value of the company. Intangible aspects such as goodwill, culture, and competences should be considered.

2.9 Planning Horizon

When an organization chooses to invest in a particular proposal, money gets tied up in that proposal— so-called “frozen assets.” The economic impact of frozen assets tends to start high and decreases over time. On the other hand, operating and maintenance costs of elements associated with the proposal tend to start low but increase over time. The total cost of the proposal—that is, owning and operating a product—is the sum of those two costs. Early on, frozen asset costs dominate; later, the operating and maintenance costs dominate. There is a point in time where the sum of the costs is minimized; this is called the minimum cost lifetime.

To properly compare a proposal with a fouryear life span to a proposal with a six-year life span, the economic effects of either cutting the six-year proposal by two years or investing the profits from the four-year proposal for another two years need to be addressed. The planning horizon, sometimes known as the study period, is the consistent time frame over which proposals are considered. Effects such as software lifetime will need to be factored into establishing a planning horizon. Once the planning horizon is established, several techniques are available for putting proposals with different life spans into that planning horizon.

2.10 Price and Pricing

A price is what is paid in exchange for a good or service. Price is a fundamental aspect of financial modeling and is one of the four Ps of the marketing mix. The other three Ps are product, promotion, and place. Price is the only revenue-generating element amongst the four Ps; the rest are costs.

Pricing is an element of finance and marketing. It is the process of determining what a company will receive in exchange for its products. Pricing factors include manufacturing cost, market placement, competition, market condition, and quality of product. Pricing applies prices to products and services based on factors such as fixed amount, quantity break, promotion or sales campaign, specific vendor quote, shipment or invoice date, combination of multiple orders, service offerings, and many others. The needs of the consumer can be converted into demand only if the consumer has the willingness and capacity to buy the product. Thus, pricing is very important in marketing. Pricing is initially done during the project initiation phase and is a part of “go” decision making.

2.11 Cost and Costing

A cost is the value of money that has been used up to produce something and, hence, is not available for use anymore. In economics, a cost is an alternative that is given up as a result of a decision.

A sunk cost is the expenses before a certain time, typically used to abstract decisions from expenses in the past, which can cause emotional hurdles in looking forward. From a traditional economics point of view, sunk costs should not be considered in decision making. Opportunity cost is the cost of an alternative that must be forgone in order to pursue another alternative.

Costing is part of finance and product management. It is the process to determine the cost based on expenses (e.g., production, software engineering, distribution, rework) and on the target cost to be competitive and successful in a market. The target cost can be below the actual estimated cost. The planning and controlling of these costs (called cost management) is important and should always be included in costing.

An important concept in costing is the total cost of ownership (TCO). This holds especially for software, because there are many not-so-obvious costs related to SPLC activities after initial product development. TCO for a software product is defined as the total cost for acquiring, activating, and keeping that product running. These costs can be grouped as direct and indirect costs. TCO is an accounting method that is crucial in making sound economic decisions.

2.12 Performance Measurement

Performance measurement is the process whereby an organization establishes and measures the parameters used to determine whether programs, investments, and acquisitions are achieving the desired results. It is used to evaluate whether performance objectives are actually achieved; to control budgets, resources, progress, and decisions; and to improve performance.

2.13 Earned Value Management

Earned value management (EVM) is a project management technique for measuring progress based on created value. At a given moment, the results achieved to date in a project are compared with the projected budget and the planned schedule progress for that date. Progress relates already-consumed resources and achieved results at a given point in time with the respective planned values for the same date. It helps to identify possible performance problems at an early stage. A key principle in EVM is tracking cost and schedule variances via comparison of planned versus actual schedule and budget versus actual cost. EVM tracking gives much earlier visibility to deviations and thus permits corrections earlier than classic cost and schedule tracking that only looks at delivered documents and products.

2.14 Termination Decisions

Termination means to end a project or product. Termination can be preplanned for the end of a long product lifetime (e.g., when foreseeing that a product will reach its lifetime) or can come rather spontaneously during product development (e.g., when project performance targets are not achieved). In both cases, the decision should be carefully prepared, considering always the alternatives of continuing versus terminating. Costs of different alternatives must be estimated—covering topics such as replacement, information collection, suppliers, alternatives, assets, and utilizing resources for other opportunities. Sunk costs should not be considered in such decision making because they have been spent and will not reappear as a value.

2.15 Replacement and Retirement Decisions

A replacement decision is made when an organization already has a particular asset and they are considering replacing it with something else; for example, deciding between maintaining and supporting a legacy software product or redeveloping it from the ground up. Replacement decisions use the same business decision process as described above, but there are additional challenges: sunk cost and salvage value. Retirement decisions are also about getting out of an activity altogether, such as when a software company considers not selling a software product anymore or a hardware manufacturer considers not building and selling a particular model of computer any longer. Retirement decision can be influenced by lock-in factors such as technology dependency and high exit costs.

3 Risk and Uncertainty

3.1 Goals, Estimates, and Plans

Goals in software engineering economics are mostly business goals (or business objectives). A business goal relates business needs (such as increasing profitability) to investing resources (such as starting a project or launching a product with a given budget, content, and timing). Goals apply to operational planning (for instance, to reach a certain milestone at a given date or to extend software testing by some time to achieve a desired quality level—see Key Issues in the Software Testing KA) and to the strategic level (such as reaching a certain profitability or market share in a stated time period).

An estimate is a well-founded evaluation of resources and time that will be needed to achieve stated goals (see Effort, Schedule, and Cost Estimation in the Software Engineering Management KA and Maintenance Cost Estimation in the Software Maintenance KA). A software estimate is used to determine whether the project goals can be achieved within the constraints on schedule, budget, features, and quality attributes. Estimates are typically internally generated and are not necessarily visible externally. Estimates should not be driven exclusively by the project goals because this could make an estimate overly optimistic. Estimation is a periodic activity; estimates should be continually revised during a project.

A plan describes the activities and milestones that are necessary in order to reach the goals of a project (see Software Project Planning in the Software Engineering Management KA). The plan should be in line with the goal and the estimate, which is not necessarily easy and obvious— such as when a software project with given requirements would take longer than the target date foreseen by the client. In such cases, plans demand a review of initial goals as well as estimates and the underlying uncertainties and inaccuracies. Creative solutions with the underlying rationale of achieving a win-win position are applied to resolve conflicts.

To be of value, planning should involve consideration of the project constraints and commitments to stakeholders. Figure 12.4 shows how goals are initially defined. Estimates are done based on the initial goals. The plan tries to match the goals and the estimates. This is an iterative process, because an initial estimate typically does not meet the initial goals.

3.2 Estimation Techniques

Estimations are used to analyze and forecast the resources or time necessary to implement requirements (see Effort, Schedule, and Cost Estimation in the Software Engineering Management KA and Maintenance Cost Estimation in the Software Maintenance KA). Five families of estimation techniques exist:

- Expert judgment

- Analogy

- Estimation by parts

- Parametric methods

- Statistical methods.

No single estimation technique is perfect, so using multiple estimation technique is useful. Convergence among the estimates produced by different techniques indicates that the estimates are probably accurate. Spread among the estimates indicates that certain factors might have been overlooked. Finding the factors that caused the spread and then reestimating again to produce results that converge could lead to a better estimate.

3.3 Addressing Uncertainty

Because of the many unknown factors during project initiation and planning, estimates are inherently uncertain; that uncertainty should be addressed in business decisions. Techniques for addressing uncertainty include

- consider ranges of estimates

- analyze sensitivity to changes of assumptions

- delay final decisions.

3.4 Prioritization

Prioritization involves ranking alternatives based on common criteria to deliver the best possible value. In software engineering projects, software requirements are often prioritized in order to deliver the most value to the client within constraints of schedule, budget, resources, and technology, or to provide for building product increments, where the first increments provide the highest value to the customer (see Requirements Classification and Requirements Negotiation in the Software Requirements KA and Software Life Cycle Models in the Software Engineering Process KA).

3.5 Decisions under Risk

Decisions under risk techniques are used when the decision maker can assign probabilities to the different possible outcomes (see Risk Management in the Software Engineering Management KA). The specific techniques include

- expected value decision making

- expectation variance and decision making

- Monte Carlo analysis

- expected value of perfect information.

3.6 Decisions under Uncertainty

Decisions under uncertainty techniques are used when the decision maker cannot assign probabilities to the different possible outcomes because needed information is not available (see Risk Management in the Software Engineering Management KA). Specific techniques include

- Laplace Rule

- Maximin Rule

- Maximax Rule

- Hurwicz Rule

- Minimax Regret Rule.

4 Economic Analysis Methods

4.1 For-Profit Decision Analysis

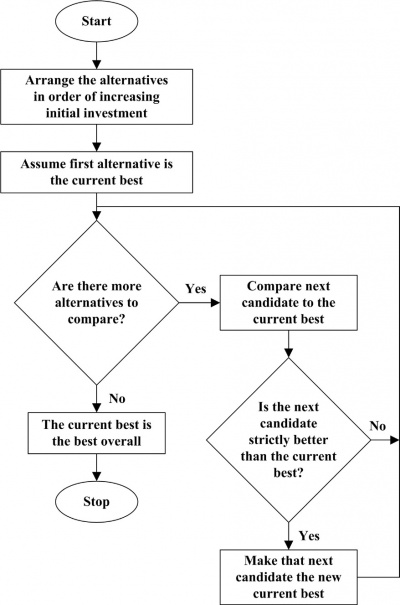

Figure 12.5 describes a process for identifying the best alternative from a set of mutually exclusive alternatives. Decision criteria depend on the business objectives and typically include ROI (see section 4.3, Return on Investment) or Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) (see section 4.4, Return on Capital Employed).

For-profit decision techniques don’t apply for government and nonprofit organizations. In these cases, organizations have different goals—which means that a different set of decision techniques are needed, such as cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness analysis.

4.2 Minimum Acceptable Rate of Return

The minimum acceptable rate of return (MARR) is the lowest internal rate of return the organization would consider to be a good investment. Generally speaking, it wouldn’t be smart to invest in an activity with a return of 10% when there’s another activity that’s known to return 20%. The MARR is a statement that an organization is confident it can achieve at least that rate of return. The MARR represents the organization’s opportunity cost for investments. By choosing to invest in some activity, the organization is explicitly deciding to not invest that same money somewhere else. If the organization is already confident it can get some known rate of return, other alternatives should be chosen only if their rate of return is at least that high. A simple way to account for that opportunity cost is to use the MARR as the interest rate in business decisions. An alternative’s present worth evaluated at the MARR shows how much more or less (in present- day cash terms) that alternative is worth than investing at the MARR.

4.3 Return on Investment

Return on investment (ROI) is a measure of the profitability of a company or business unit. It is defined as the ratio of money gained or lost (whether realized or unrealized) on an investment relative to the amount of money invested. The purpose of ROI varies and includes, for instance, providing a rationale for future investments and acquisition decisions.

4.4 Return on Capital Employed

The return on capital employed (ROCE) is a measure of the profitability of a company or business unit. It is defined as the ratio of a gross profit before taxes and interest (EBIT) to the total assets minus current liabilities. It describes the return on the used capital.

4.5 Cost-Benefit Analysis

Cost-benefit analysis is one of the most widely used methods for evaluating individual proposals. Any proposal with a benefit-cost ratio of less than 1.0 can usually be rejected without further analysis because it would cost more than the benefit. Proposals with a higher ratio need to consider the associated risk of an investment and compare the benefits with the option of investing the money at a guaranteed interest rate (see section 4.2, Minimum Acceptable Rate of Return).

4.6 Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Cost-effectiveness analysis is similar to costbenefit analysis. There are two versions of costeffectiveness analysis: the fixed-cost version maximizes the benefit given some upper bound on cost; the fixed-effectiveness version minimizes the cost needed to achieve a fixed goal.

4.7 Break-Even Analysis

Break-even analysis identifies the point where the costs of developing a product and the revenue to be generated are equal. Such an analysis can be used to choose between different proposals at different estimated costs and revenue. Given estimated costs and revenue of two or more proposals, break-even analysis helps in choosing among them.

4.8 Business Case

The business case is the consolidated information summarizing and explaining a business proposal from different perspectives for a decision maker (cost, benefit, risk, and so on). It is often used to assess the potential value of a product, which can be used as a basis in the investment decisionmaking process. As opposed to a mere profitloss calculation, the business case is a “case” of plans and analyses that is owned by the product manager and used in support of achieving the business objectives.

4.9 Multiple Attribute Evaluation

The topics discussed so far are used to make decisions based on a single decision criterion: money. The alternative with the best present worth, the best ROI, and so forth is the one selected. Aside from technical feasibility, money is almost always the most important decision criterion, but it’s not always the only one. Quite often there are other criteria, other “attributes,” that need to be considered, and those attributes can’t be cast in terms of money. Multiple attribute decision techniques allow other, nonfinancial criteria to be factored into the decision.

There are two families of multiple attribute decision techniques that differ in how they use the attributes in the decision. One family is the “compensatory,” or single-dimensioned, techniques. This family collapses all of the attributes onto a single figure of merit. The family is called compensatory because, for any given alternative, a lower score in one attribute can be compensated by—or traded off against—a higher score in other attributes. The compensatory techniques include

- nondimensional scaling

- additive weighting

- analytic hierarchy process.

In contrast, the other family is the “noncompensatory,” or fully dimensioned, techniques. This family does not allow tradeoffs among the attributes. Each attribute is treated as a separate entity in the decision process. The noncompensatory techniques include

- dominance

- satisficing

- lexicography.

4.10 Optimization Analysis

The typical use of optimization analysis is to study a cost function over a range of values to find the point where overall performance is best. Software’s classic space-time tradeoff is an example of optimization; an algorithm that runs faster will often use more memory. Optimization balances the value of the faster runtime against the cost of the additional memory.

Real options analysis can be used to quantify the value of project choices, including the value of delaying a decision. Such options are difficult to compute with precision. However, awareness that choices have a monetary value provides insight in the timing of decisions such as increasing project staff or lengthening time to market to improve quality.

5 Practical Considerations

5.1 The “Good Enough” Principle

Often software engineering projects and products are not precise about the targets that should be achieved. Software requirements are stated, but the marginal value of adding a bit more functionality cannot be measured. The result could be late delivery or too-high cost. The “good enough” principle relates marginal value to marginal cost and provides guidance to determine criteria when a deliverable is “good enough” to be delivered. These criteria depend on business objectives and on prioritization of different alternatives, such as ranking software requirements, measurable quality attributes, or relating schedule to product content and cost.

The RACE principle (reduce accidents and control essence) is a popular rule towards good enough software. Accidents imply unnecessary overheads such as gold-plating and rework due to late defect removal or too many requirements changes. Essence is what customers pay for. Software engineering economics provides the mechanisms to define criteria that determine when a deliverable is “good enough” to be delivered. It also highlights that both words are relevant: “good” and “enough.” Insufficient quality or insufficient quantity is not good enough.

Agile methods are examples of “good enough” that try to optimize value by reducing the overhead of delayed rework and the gold plating that results from adding features that have low marginal value for the users (see Agile Methods in the Software Engineering Models and Methods KA and Software Life Cycle Models in the Software Engineering Process KA). In agile methods, detailed planning and lengthy development phases are replaced by incremental planning and frequent delivery of small increments of a deliverable product that is tested and evaluated by user representatives.

5.2 Friction-Free Economy

Economic friction is everything that keeps markets from having perfect competition. It involves distance, cost of delivery, restrictive regulations, and/or imperfect information. In high-friction markets, customers don’t have many suppliers from which to choose. Having been in a business for a while or owning a store in a good location determines the economic position. It’s hard for new competitors to start business and compete. The marketplace moves slowly and predictably. Friction-free markets are just the reverse. New competitors emerge and customers are quick to respond. The marketplace is anything but predictable. Theoretically, software and IT are frictionfree. New companies can easily create products and often do so at a much lower cost than established companies, since they need not consider any legacies. Marketing and sales can be done via the Internet and social networks, and basically free distribution mechanisms can enable a ramp up to a global business. Software engineering economics aims to provide foundations to judge how a software business performs and how friction-free a market actually is. For instance, competition among software app developers is inhibited when apps must be sold through an app store and comply with that store’s rules.

5.3 Ecosystems

An ecosystem is an environment consisting of all the mutually dependent stakeholders, business units, and companies working in a particular area. In a typical ecosystem, there are producers and consumers, where the consumers add value to the consumed resources. Note that a consumer is not the end user but an organization that uses the product to enhance it. A software ecosystem is, for instance, a supplier of an application working with companies doing the installation and support in different regions. Neither one could exist without the other. Ecosystems can be permanent or temporary. Software engineering economics provides the mechanisms to evaluate alternatives in establishing or extending an ecosystem—for instance, assessing whether to work with a specific distributor or have the distribution done by a company doing service in an area.

5.4 Offshoring and Outsourcing

Offshoring means executing a business activity beyond sales and marketing outside the home country of an enterprise. Enterprises typically either have their offshoring branches in lowcost countries or they ask specialized companies abroad to execute the respective activity. Offshoring should therefore not be confused with outsourcing. Offshoring within a company is called captive offshoring. Outsourcing is the result-oriented relationship with a supplier who executes business activities for an enterprise when, traditionally, those activities were executed inside the enterprise. Outsourcing is site-independent. The supplier can reside in the neighborhood of the enterprise or offshore (outsourced offshoring). Software engineering economics provides the basic criteria and business tools to evaluate different sourcing mechanisms and control their performance. For instance, using an outsourcing supplier for software development and maintenance might reduce the cost per hour of software development, but increase the number of hours and capital expenses due to an increased need for monitoring and communication. (For more information on offshoring and outsourcing, see “Outsourcing” in Management Issues in the Software Maintenance KA.)

A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) [4].

The PMBOK® Guide provides guidelines for managing individual projects and defines project management related concepts. It also describes the project management life cycle and its related processes, as well as the project life cycle. It is a globally recognized guide for the project management profession.

Software Extension to the Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (SWX) [5].

SWX provides adaptations and extensions to the generic practices of project management documented in the PMBOK® Guide for managing software projects. The primary contribution of this extension to the PMBOK® Guide is description of processes that are applicable for managing adaptive life cycle software projects.

B.W. Boehm, Software Engineering Economics [6].

This book is the classic reading on software engineering economics. It provides an overview of business thinking in software engineering. Although the examples and figures are dated, it still is worth reading.

C. Ebert and R. Dumke, Software Measurement [7].

This book provides an overview on quantitative methods in software engineering, starting with measurement theory and proceeding to performance management and business decision making.

D.J. Reifer, Making the Software Business Case: Improvement by the Numbers [8].

This book is a classic reading on making a business case in the software and IT businesses. Many useful examples illustrate how the business case is formulated and quantified.

[1] S. Tockey, Return on Software: Maximizing the Return on Your Software Investment, Addison-Wesley, 2004.

[2] J.H. Allen et al., Software Security Engineering: A Guide for Project Managers, Addison-Wesley, 2008.

[3] R.E. Fairley, Managing and Leading Software Projects, Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press, 2009.

[4] Project Management Institute and IEEE Computer Society, Metrics and Models in Software Quality Engineering, 5th ed., Project Management Institute, 2013.

[5] Project Management Institute and IEEE Computer Society, Software Extension to the PMBOK® Guide Fifth Edition, ed:, Project Management Institute, 2013.

[6] B.W. Boehm, Software Engineering Economics, Prentice-Hall, 1981.

[7] C. Ebert and R. Dumke, Software Measurement, Springer, 2007.

[8] D.J. Reifer, Making the Software Business Case: Improvement by the Numbers, , Addison Wesley, 2002.